Edinburgh has always felt like a cultural city to me. As a child, my family and I visited often, and I remember being mesmerized by Edinburgh Castle, mostly because it was a castle, but also because it was built on top of a mountain and looked so dramatic to me. There’s something fascinating about revisiting a place you knew as a child, but through adult eyes.

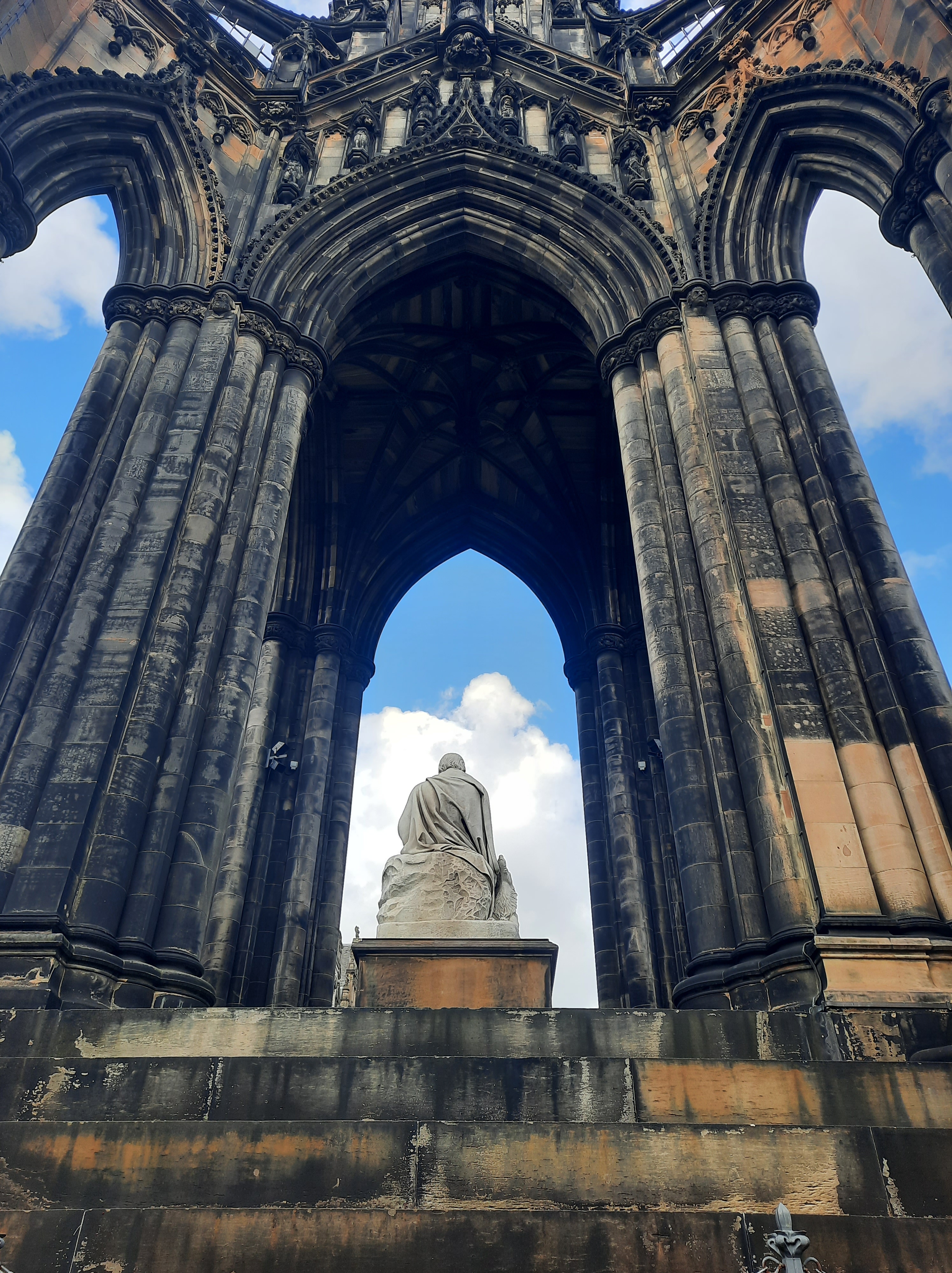

It wasn’t until much later that I understood the significance of landmarks like the towering gothic monument to Sir Walter Scott. As a child, it was just an impressive structure to me; as an adult, I realized the importance of Sir Walter Scott in Scottish literature, and then when I discovered that one of my own names, Rowena, came from his most famous novel, Ivanhoe.

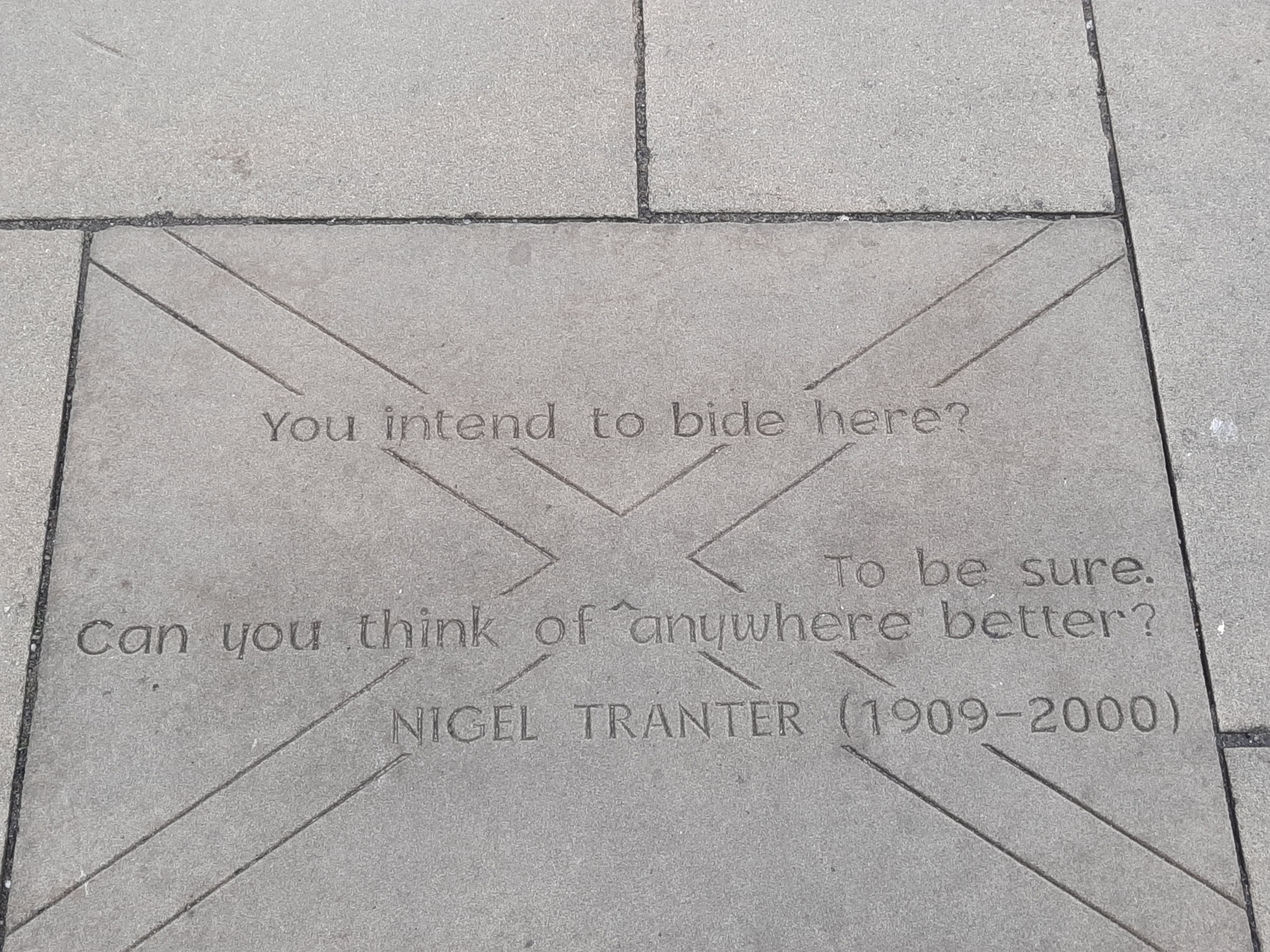

One place I always find fascinating as a writer is the Writers’ Museum, dedicated to the lives and works of arguably three of Scotland’s most famous writers: Robert Burns, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Sir Walter Scott. Even before stepping inside, I was struck by the quotes etched in stone in the courtyard, quotes from renowned Scottish authors. Their words made me pause and reflect on Scotland’s place in my life and in my heart, especially as a writer. I understood their sentiment; the inspiration that a country can put in your heart, the fact that your childhood home will never leave you. I learned to read in Scotland, I fell in love with books there. I grew up on the works of Scottish writers and recited Burns’ poems aloud with my classmates in primary school. For someone whose life and work revolves around words, visiting the museum almost feels like a homecoming.

You can see personal artifacts belonging to the writers, including Robert Burns’ writing desk and personal letters, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s copy of Montesquieu. And we are so lucky that we can visit for free. There is also an amazing gift shop which is your place to stock up on literary gifts and postcards for yourself and fellow bookworms.

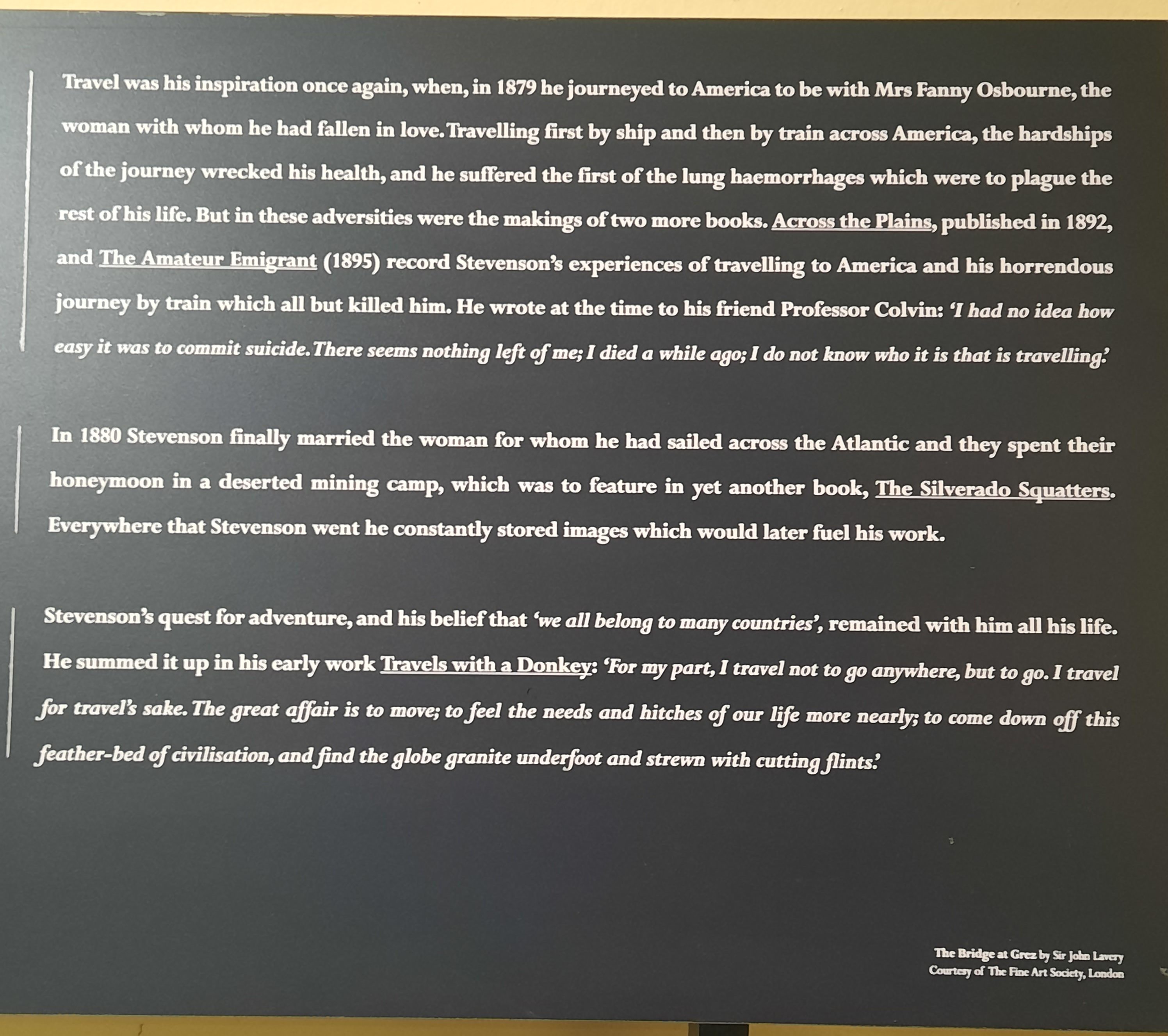

I had a copy of Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses as a child, and I read the abridged version of Treasure Island so many times that I memorized parts of it. Of all the exhibits in the Writers’ Museum, it was Stevenson’s that moved me the most. I felt an undeniable connection, not just to his words, but to his spirit. His sense of adventure, his love of travel, and his reflective nature spoke to me. He wasn’t just a novelist, he was a travel writer, too, and that kinship struck a deep chord with me.

One quote of his in particular stayed with me, and it seems so reflective of my own life in many ways. This is what he wrote:

“It is not in vain that I return to the nothings of my childhood; for every one of them has left some stamp upon me or put some fetter on my boasted free-will. In the past is my present fate; and in my past also is my real life.”

Those words resonated profoundly. They helped me understand something I’d long felt but hadn’t yet found the language for, and this is the fact that who we are is a result of where we’ve been, and that our childhoods shape every story we tell.

What I learned was visiting a place like the Writers’ Museum is more than just an opportunity to admire “writer’s debris”, as Patti Smith once put it, depending on the place it can actually be an invitation to pause and reflect on how your own life and experiences have been shaped by the world around you. It’s usually not until you are older that you understand this fact, and I wasn’t expecting that revelation at the Writers’ Museum, but it’s fitting that that’s where I got this moment of clarity.

Leave a Reply